+ Andrea van Beausichem, Andrea van Beusichem, Birds, Coots, Ducks, eagles, egret, Fish, Geese, heron, Migration, Montezuma, natural, osprey, sludge, swans, Uncategorized

Montezuma Waterfowl Refuge?

Unfortunately, current practices would indicate that this is an appropriate name change for the (former?) Montezuma National Wildlife Refuge. For the past three years each of its marsh pools have been sequentially groomed to promote a plant-based ecosystem to encourage the waterfowl population — ducks, geese, and swans, but primarily ducks. This strategy, however, has decimated the fish habitat upon which water waders depend; these include such well-known species as herons (green, black-crowned, and great blues) and egrets. It has forced these and other resident wildlife, including osprey, eagles, and kingfishers, to seek new sources of food elsewhere. The Wildlife Drive attracts a large number of visitors each year, but at the time of this writing (May 24, 2021) it features only long stretches of mud flats littered with the odoriferous bodies of decomposing fish.

Once the pool was flooded, this vegetation became duck food. Photo courtesy of https://nohomenomadder.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/11/montezuma-10-1024×576.jpg

Andrea van Beusichem, Visitor Services Manager at MNWR, explained the pool drainage policy to readers of the Friends of Montezuma National Wildlife Refuge Facebook page. Even though she believes that “[b]iological diversity leads to a healthy ecosystem” she admits that the drainage has a single and restrictive purpose. “[It exposes the marsh bed] to the warmth needed for plant growth.” Rather than express concern for the heartless elimination of the fish habitat, Ms. van Beusichem evidently believes that the carnage affects only carp, an unwanted and invasive species. “[T]he dead carp are being eaten by migratory birds. . .their carcasses are consumed by bald eagles. Carcasses will also by eaten by turkey vulture[s], another migratory bird.” However, direct observation reveals that this is not the case. The extensive mud flats that comprise what was once the main pool are littered with dead fish and other water-dwellers. Even though many photos are posted on Joseph Karpinski’s Facebook site, Birds of Montezuma National Wildlife Refuge, only two show eagles pecking at dead carp, and there was a single, recently posted 30-second video (now removed) of two turkey vultures circling in the thermals arising over the mud flats. No significant numbers of vultures or eagles are evident, either in photos or upon observation (at least by this writer), and the carcasses remain largely untouched. No other photos or videos show any other predators feasting upon the dead carp. But there are several photos of great blue herons and egrets ignoring the carrion surrounding them while searching in vain for live food.

Photo courtesy of Debra Muska, https://www.facebook.com/photo?fbid=1920404608110019&set=g.172217523476266

Yet Ms. van Beusichem continues to dismiss the fish kill and its consequences. The droughts, she explains, simply “mimic the natural [weather] cycle.” The carp are not subjects of mass slaughter; instead, they are being “managed” by the drainage policies. Such policies, she states, are necessary to “rejuvenate the marshes” to “allow new plant growth.” And therein lies the problem. By focusing on a plant-only ecosystem, the fish-eaters lose their food supply. Carp aren’t the only fish that die when the marshes are “rejuvenated.” ALL the fish die, as do frogs and other water-dwellers, depriving the waders and hunters of their food source. True, some will find new fishing grounds, but others will starve to death.

My question is, why the focus on a plant-based ecosystem to the detriment of a formerly coexistent fish habitat?

Back in the days before drainage. Photo courtesy of https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb

There are two reasons why this question remains unanswered. The first (and most obvious) is that Ms. van Beusichem can’t provide an answer. According to her Facebook page, she is a functional nutritionist, a bootcamp-style coach, and a certified turbo-kick live instructor, but she has no training in biology, ecosystems, or marsh management, even though “anything that has to do with the public at the Refuge, I deal with.” She is a spokesperson and nothing more. What she says is for public relations purposes only.

The other, less obvious reason is that she won’t provide an answer, probably because there is a contributing MNWR partner with an intense interest in maintaining the Refuge as a duck-only environment. This partner, Ducks Unlimited, is self-described as “the world’s largest nonprofit organization dedicated to conserving North America’s continually disappearing waterfowl habitats.” Their interest and focus are clearly on ducks — not herons, not eagles, and certainly not any other fish-eating species. They are interested only in ducks and duck habitats. Period.

Ducks Unlimited has provided both labor and financing to the Montezuma Wetlands Complex, which includes, according to the New York Department of Environmental Conservation, the approximately 10,000 acres comprising The Montezuma National Wildlife Refuge as well as its Visitor Center. So, while draining the pools at MNWR may disappoint its visitors by polluting Wildlife Drive with noxious odors and offering unlimited views of mud, it is certain to delight the members of Ducks Unlimited, who anticipate lush duck-attracting vegetation come fall. I have no doubt that these policies, which foster a duck-only habitat, will also foster a long-lasting partnership between Ducks Unlimited and MNWR.

Why is hunting allowed at a refuge? This photo of an MNWR duck kill comes courtesy of https://www.fieldandstream.com/app/uploads/2019/01/18/RYXECODJE3DYPCHAU4H2N72WMQ.jpg

This issue is further complicated by the fact that the Montezuma National Wildlife Refuge allows onsite duck hunting. Hunting as a “recreation” — at a refuge? which is supposed to be a safe place for wildlife? While this practice may be a holdover from a 1930s philosophy, it is important to note that it isn’t 1930 any longer. Today, in 2021, the US Department of the Interior defines the term “national wildlife refuge” without even mentioning hunting — and for good reason:

A national wildlife refuge is a designation for certain protected areas that are managed by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. These public lands and waters are set aside to conserve America’s wild animals and plants. On top of that, they provide enjoyment and beauty, and they demonstrate shared American values that support protecting and respecting living things.

National refuges, according to this definition (https://www.doi.gov/blog/celebrating-national-wildlife-refuges), were established to protect and conserve wildlife, a fact that seems to be lost upon MNWR officials and Ducks Unlimited. In any event, “protecting and respecting living things” notwithstanding, Field and Stream ( https://www.fieldandstream.com/breaking-ice-mallards-on-montezuma-national-wildlife-refuge/), explains the policy that Ms. van Beusichem fails to address:

This patchwork of 10,000 federal acres is the first U.S. layover for more than 1 million Atlantic Flyway waterfowl on their fall migration south. Open to duck hunters every Tuesday, Thursday, and Saturday during the season, Montezuma requires a reservation, made three days prior to your hunt day.

The dictionary definition of “conserve” is “to protect. . .to keep in a safe and sound state,” and Ducks Unlimited claims to be an organization of “conservationists.” However, they boast that “the majority of its members are hunters,” and they defend duck hunting, which they prefer to call “harvesting,” in unequivocal terms:

The dictionary definition of “conserve” is “to protect. . .to keep in a safe and sound state,” and Ducks Unlimited claims to be an organization of “conservationists.” However, they boast that “the majority of its members are hunters,” and they defend duck hunting, which they prefer to call “harvesting,” in unequivocal terms:

Wildlife management, hunting, and habitat conservation in North America are interdependent, and Ducks Unlimited, Inc. strongly supports hunting. The financial contributions of hunters and recreational shooters, through mechanisms such as their hunting licenses and excise taxes on sporting arms and ammunition, provide the foundation for conservation funding. . .

https://www.ducks.org/about-ducks-unlimited/du-position-on-hunting

I’m not sure how I feel about hunting. Certainly in times of natural overabundance, a quick death due to a shot in the head is better than a slow, agonizing death due to hunger or disease. However, I am very sure how I feel about hunting when innocent wildlife, including ducks, are lured to a safe-haven refuge, only to be considered “fair game” to hunters who 1) consider it a “recreation” to shoot them and 2) pay inter alia licensing fees for the privilege. This is hardly “fair game.” It is patently unfair, mercenary, and rather disgusting.

Ms. van Beusichem, though, on behalf of MNWR, remains silent on this issue.

Instead, she continues to insist that the periodic drainage “replicates nature” and is necessary for the health of the marshes. The elimination of the fish habitat in favor of providing acres of duck food promotes “biological diversity.” And, of course, she’s already told us that “[b]iological diversity leads to a healthy ecosystem.” It is my opinion that anyone who believes there is “diversity” in a duck-only habitat certainly doesn’t know the meaning of the word. And if we are to believe her when she assures us that swarms of turkey vultures and eagles will clear up the dead fish component of this “healthy ecosystem,” then we must disbelieve our own eyes. And noses. (And what about the absent herons and egrets?)

Instead, she continues to insist that the periodic drainage “replicates nature” and is necessary for the health of the marshes. The elimination of the fish habitat in favor of providing acres of duck food promotes “biological diversity.” And, of course, she’s already told us that “[b]iological diversity leads to a healthy ecosystem.” It is my opinion that anyone who believes there is “diversity” in a duck-only habitat certainly doesn’t know the meaning of the word. And if we are to believe her when she assures us that swarms of turkey vultures and eagles will clear up the dead fish component of this “healthy ecosystem,” then we must disbelieve our own eyes. And noses. (And what about the absent herons and egrets?)

In fairness, she does offer us an apology of sorts:

We have to make choices. Based on mandates and missions, those choices use the best science available to create, enhance, protect, and monitor habitat for federally threatened and endangered species (none currently exist on the refuge), migratory fish (none currently exist on the refuge), and migratory birds (about 300 species exist on the refuge).”

What happens to fish-eaters in a plant-based ecosystem. Photo courtesy Kelly’s Critters, https://www.facebook.com/photo?fbid=487037629175780&set=g.172217523476266

An apology, that is, only until you realize that she just about quotes the BASI mandate of the Migratory Bird Act, which was designed to protect wildlife, not to endorse practices that drive them away through habitat elimination.

But I digress.

So, not only are we asked to disbelieve our eyes, we are to be comforted by the fact that the Refuge uses “the best science available” — not to protect endangered species (none currently exist on the refuge) but instead to create a twice-yearly landing zone for migrating ducks, which are then targeted and killed by any duck hunter with enough money to pay the requisite licensing (and other?) fees and enough smarts to make an advance reservation.

Too-frequent drainage, natural or otherwise, will encourage growth of shrubs and trees rather than grass. The Knox Marsellus marsh was “restored” in 2006, a joint effort of the Montezuma Complex and Ducks Unlimited. Why am I not surprised?

It always makes me sigh when the destruction caused by human interference is defended by claims of “best science available” and “best interests” of the wildlife. It also makes me furious when marsh managers overuse standard maintenance practices such as ditching and drainage so that the emergent marsh environment they claim to protect remains predominantly in the vegetative stage — with only brief periods that allow the fish to return before repeating the cycle once more. In fact, Michigan State University, which studies the state’s Natural Features Inventory, warns against a too-frequent drainage cycle because it “allow[s] shrubs and trees to establish and eventually replace emergent marshes” — which appears to be occurring right now at the Knox-Marcellus marsh, in spite of — but more likely because of — the joint efforts of the Montezuma Complex and Ducks Unlimited.

A once-common but now rare sight at MNWR. There just isn’t enough water to support more than one or two egrets. . . or herons. . .or eagles. . .or osprey. . . the list of vanishing wildlife is a long one.

Furthermore, the University studies point out that “[e]mergent marshes flood seasonally, especially in the spring.” Such flooding, they state, provides “. . .spawning grounds for fish.” Instead of mimicking the natural cycle of springtime flooding, which would encourage a coexistent fish-based ecosystem, the MNWR managers choose instead to do the exact opposite by draining the main pool down to mud flats — which they have been doing annually since 2018. This prevents the fish from spawning and eventually kills them, which in turn displaces the wildlife dependent upon them for sustenance. Here in the northeast droughts don’t usually occur annually and are most likely to occur in the early summer. Waiting until then to replicate the natural cycle of drought would make more sense, but it would not allow enough time for sufficient vegetative growth and subsequent flooding to accommodate the fall duck migration — and its concomittant hunting season.

Is the Flyway limited to ducks? It will be if MNWR and Ducks Unlimited have their way. As I write this, the fish-eating portion of the claimed 300 species of migratory birds are fleeing the Refuge, a recognized Flyway pit stop, because their habitat has been eliminated in favor of ducks.

Maybe they should just rename the refuge, “Montezuma National WATERFOWL Refuge, because that is what it is.

Grainy photo courtesy https://friendsofmontezuma.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/DUCKS-MAIN-02-111120-scaled.jpg

Ms. Beusichem and companion celebrate St. Patrick’s Day, https://www.facebook.com/photo.php?fbid=10224630228920689&set=p b.1158995765.-2207520000..&type=3

An update, May 27: The controversy is over, at least on Joseph Karpinski’s Facebook page, Birds of Montezuma National Wildlife Refuge. He has quelled any further discussion by removing anyone who does not subscribe to the drainage policies (me) espoused by Ms. van Beusichem along with another poster (Alyssa Johnson) who perhaps too vehemently defended Ms. van Beusichem and her public relations statements. These actions were duly acknowledged by Ms. van Beusichem, who thanked Mr. Karpinski “for allowing me to explain refuge management to you all”.

Alyssa Johnson, who gives tours at the Refuge but does not work there. Photo courtesy of https://www.facebook.com/Montezuma AudubonCenter/videos/760591197808895

Well, at least the smell is gone.

The mud flats now (mid-to-late June) sport a thick covering of grassy vegetation, thanks to the fertilizer provided by mounds of dead fish, and re-flooding the main pool will likely begin in late August, thus producing the desired duck-only environment just in time for their fall migration to the south.

However, facts remain facts. This process does not “replicate nature” nor does it promote the biodiversity Ms. van Beusichem claims; instead eliminates diversity by destroying the marsh food web and creating a marsh food chain, thus eliminating the fish-eaters and the food sources upon which they depend. The large water kill they create is not limited to carp and is cruel and tortuous to all fish as well as the other water-resident species. And for what purpose? — so they can sponsor seasonal duck kills every Tuesday, Thursday, and Saturday and thereby collect a good portion of Federal Duck Stamp dollars.

Of a recent visit to MNWR, Field and Stream writes “Twenty mallards swing overhead and commit. Bard and Tietjen take out the lead drake. Minutes later, seven birds zip in, and we kill a drake and a hen.” Drake death courtesy of Mike Bard and Clay Tietjen, photo courtesy Field and Stream.

Mike Bard enjoying “recreational harvesting” of ducks at MNWR. Photo courtesy of Christopher Testani for Field and Stream.

It’s not just ducks. Geese, including snow geese, as well as land animals (turkey, deer, rabbit, and squirrel) are all considered huntable game at the Refuge. Does the Refuge make money on the kills it allows on its property? Are hunters charged a fee for their permits — beyond, of course, the mandatory yearly purchase of the Federal Duck stamp? Does MNWR charge a fee-per-pound for every dead animal?

The Montezuma National Wildlife Refuge is free to pursue this agenda, despite the damage it causes. There is nothing I (or anyone else) can do except speak for the wildlife that cannot speak for themselves.

Well, this blog has definitely been seen, because Ms. van Beusichem has now issued a brochure, Draining the Main Pool, Feeding the Waterfowl, which is available without charge at the MNWR Visitor’s Center.

Well, this blog has definitely been seen, because Ms. van Beusichem has now issued a brochure, Draining the Main Pool, Feeding the Waterfowl, which is available without charge at the MNWR Visitor’s Center.

Nice try, but in my opinion it warrants no cigar. She merely repeats the glib arguments that we have already heard, albeit with a bit more cheerfulness.

“The Montezuma National Wildlife Refuge,” she states, “was set aside for the protection of migratory birds, especially waterfowl — ducks and geese.” She does not explain why the ducks and geese enjoy favoritism over the other resident (and formerly resident) Refuge wildlife, but she does explain the lengths to which MNWR personnel will go to provide for the special needs of ducks:

Just like you and me, there are certain foods [the ducks] love that are most healthy for them. . .we make every effort to grow the plants that provide the very best food for ducks. These plants need moist soil to germinate and grow and will not come up through the water. Thus, we need to allow our marshes to dry out every so often.

Inside the folded single sheet, there are four views of the main pool, all of which feature water and none of which bear a likeness to the dry green acreage that used to be the main pool. Yet it is here, Ms. van Beusichem states, where “sparrows, sandhill crane[s] and others breed” (did she mean “feed?” because they don’t breed in the open meadowlands). She then assures readers that the marsh managers “provide habitat for other wildlife as well, like muskrats, terns, great blue herons and many other species that need water through the summer.” There are no photos to substantiate this claim, other than tiny, grainy, undated insets of the aforementioned animals that were clearly taken in better, wetter days.

As the water slowly drained away, the carnage became obvious, both to the eye and the nose; however, none of this is shown or even mentioned in the brochure.

The brochure, an 8-1/2 x 11″ sheet folded lengthwise, looks like it was prepared on a home printer. It is so grainy I could not get a decent photo of it to reproduce here. In any event, it does nothing to inspire confidence in either Ms. van Beusichem or the marsh management she tries to defend. The language is annoyingly simplistic, and the featured views bear no resemblance to the water-barren meadows that cover what was once the main pool bottom. The muskrats, herons, and “many other species” she claims are provided for no longer reside at the Refuge because there is no water to support their feeding habits and/or lifestyle. No mention is made of the destruction of the fish ecosystem or the death, carnage, odors, and mass exodus of the fish-eaters that resulted from the creation of a duck-only habitat — it’s as if none of that ever happened.

However, in Ms. van Beusichem’s world, it all ends happily ever after for her readers and the ducks, because “Come fall, water will be added to the Main Pool once again so the ducks can get to their feast!”

But it’s not shooting innocent animals, it’s “harvesting” them. And the US FWS, which oversees national wildlife refuges (including the one at Montezuma) agrees. https://usfws.medium.com/fall-harvest-traditions-meals-and-foraging-on-refuges-f7fe1fafa1c2

After which they will be shot and killed by members of Ducks Unlimited.

Writing on Joseph Karpinksi’s Facebook Page, Birds of Montezuma National Wildlife Refuge, MNWR spokesperson Andrea van Beusichem advised visitors that Wildlife Drive will be “challenging” this year. I’m not sure if that is the best way to describe it. . .pathetic is more like it. There just isn’t much to see on the grasslands situated where the marshes used to be.

But hey, at least it doesn’t stink like it did back in May! The decomposed fish carcasses that littered the mud flats have fertilized and fed the lush vegetation that now covers the various dried-up pools, including the large one near the Visitors Center and (for the third year in a row) the main pool.

Juvenile eagle — too young to realize he won’t find fish in the “main pool,” which is now only a shallow transitory puddle.

The fish-eating wildlife have mostly vanished to parts unknown, but a few great blue herons, an eagle or two, and some gulls still remain. They obviously didn’t get the memo. The muskrats, beaver, otters, and snakes who lived both in and out of the water are mostly gone, too. Only the ubiquitous species remain — Canada geese, red-wing blackbirds, mallards, some painted turtles, and house sparrows are easily seen along with a few song sparrows, a rare killdeer, and an even rarer yellowlegs. The celebrated sandhill cranes remain, too, but they roam so far out on what used to be the main pool they are visible only as little-dots-with-necks, even with an 800 mm equivalent lens.

No water at MNWR? No problem! This beautiful trumpeter found better (wetter) accommodations on the east-side marsh on Rt 89 in South Butler. (The rookery has been abandoned, but the eagles built a nest nearby.)

However, land animals are starting to make their appearance, especially in the early mornings. Last year when the main pool was just as dry I spotted a coyote emerging from the dried-up ditch that runs along the west side of the Drive. One morning last week I was following a gentleman from Pennsylvania who was staring so intently at the dots-with-necks way across the main-pool meadow that he missed entirely a young doe who was standing right in front of us, checking out our cars.

Actually, I feel bad when I see so many out-of-state cars. I’ve seen people from Pennsylvania, Massachusetts, Connecticut, and New Jersey who obviously didn’t get the memo, either. It’s too bad, especially with the price of gas these days, for visitors to travel 7 or 10 hours (one way) only to find that Wildlife Drive has become Wildlife Dried.

A curious young lady, taken through the windshield so as not to scare her away.

Still, I never consider it a waste of time (or gasoline) seeking wildlife to photograph. I am one of the fortunate ones who drive down Route 89 South, where you can find wildlife anywhere from Wolcott to Butler to Savannah to Tyre, none of which depend on MNWR water levels for their sustenance — and are doing quite well because of it.

Some views from the Rt 89 Nature Corridor:

Young buck, Rt 89, Savannah

Uh-oh! Rt 89, Savannah.

Thank goodness, it was only a warning!

Guarding the nestlings from a nearby flock of pigeons. Rt 89, Tyre

Breakfast, anyone? Rt 89 Savannah

Mr and Mrs Ring-Necked Pheasant looking for breakfast in a soybean field. Rt 89, Savannah

Now some views from the Dried-Up Wildlife Drive:

Just in case they forgot, the refuge is for *wildlife*, not just ducks!

A happy little song sparrow

An itchy great blue. . . either that, or he’s looking for his keys.

Wild onion in bloom

Gotta go! Female red-wings are probably the most misidentified bird in the Northeast. . .if not in America!

Harassed by a blackbird. . . no wonder four-and-twenty of them were baked in a pie!

Last year’s coyote

A rare (for us in the Northeast!) American avocet enjoying what would prove to be the last significant water level at MNWR (2018). The pools have been drained every year since.

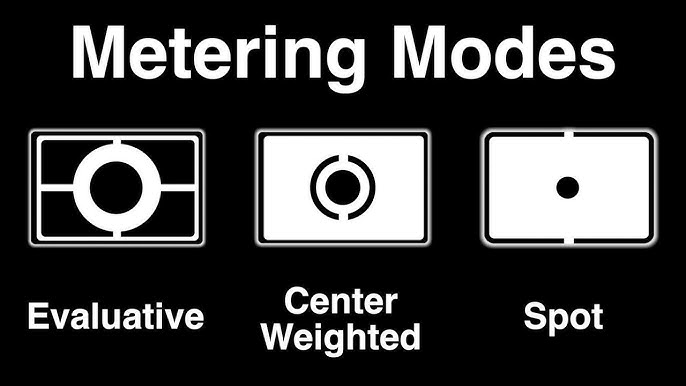

Matrix works well when each zone has enough light to naturally fall into that 18% gray area.

How?

With spot metering, of course.

I never had to bother with it before, but in retrospect I really should have.

Oh, I know how much the camera meter likes 18% gray, but I didn’t think much of it. Matrix metering — a/k/a evaluative a/k/a zone metering — is the default setting on most cameras — and for a reason. It (generally) works.

Olympus cameras are a bit snobbish. Their matrix metering is called ESP, which stands for electro-selective patterning. Arrogance aside, I like this name. In any event, it works about the same as the other-named brands.

From Olympus “Better Exposures with Spot Metering and Flash,” available on YouTube

Matrix metering works by dividing the scene into zones (“patterns” in Olympus-speak).

It evaluates the light in each zone and then calculates what it thinks (if cameras could think, that is) is a proper exposure of the combination of lights and shadows.

It works great! as long as the zones don’t vary too much.

No problem with matrix metering here! (Can you “spot” the leucistic hawk?

And if your subject pretty much fills the frame when you look through the viewfinder, you will absolutely love matrix metering!

So, as long as I could identify my subjects with a reasonable degree of certainty, I guessed I was safe in using matrix metering.

Matrix is fine when your subject fills (or nearly fills) the scene.But what if there are a lot of dark areas in your scene? and a lot of light areas as well? Averaging these into an overall 18% gray means you are going to lose either the dark shadows or the brighter areas. Which is why, by the way, you should be checking your histogram, but that’s another story.

By filling the frame with your subject you won’t have to choose how to expose the lights and darks.

In that case you will have to choose, guided by the histogram, which one to sacrifice, the lights or the darks.

Or you could choose center-weighted metering. The light meter will still evaluate all the zones, but the center zones will be given priority.

Bright sky + dark tree limbs + white blob in the center = Spot metering!

But what if your scene is full of contrasting lights and darks AND a big white blob in the center, which is going to fly away at any second?

That’s where spot metering reigns supreme.

In spot metering you point at a specific area, and the meter evaluates only the area you are pointing at.

And THAT, my friends, is why this delightfully leucistic red-tail hawk looks so delightful.

Buy one, get one free! That’s right, folks, you get TWO home sites for the price of one, both with an expansive and expensive waterfront view.

Buy one, get one free! That’s right, folks, you get TWO home sites for the price of one, both with an expansive and expensive waterfront view.

And one already has a home built on it!

But not for long. Because that already-built home is an active and well-established bald eagle nest. . .and it will not last long once home construction starts within 330′ of it.

In fact, 330′ is the minimum distance buffer zone proposed by the U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service and recognized by the New York State Department of Environmental Conservation, because “[b]ald eagles exhibit greater sensitivity to disturbance when activities occur within full view of a bird.” So if the birds can see what’s going on, the distance buffer is doubled to “660′ for most activities.” (NYS Bald Eagle Protection Plan, 2015, p. 31).

H owever, home construction is not included in these guidelines for “most activities”

owever, home construction is not included in these guidelines for “most activities”

That’s because the NYS Bald Eagle Conservation Plan (2015) recognizes construction of any building a unique circumstance that warrants its own set of guidelines. Quoting from p. 33 of the Plan, “Construction of new buildings, roads, utilities or other permanent structures is not recommended within ¼ mile, or 1320 feet of an eagle nest, if there is no visual buffer.”

Furthermore,

“If a visual buffer exists and the activity/feature is not visible from the nest, such activities should not occur within 660 feet of the nest site.”

What visual buffer? I don’t see one here on this property.

So, if I understand this correctly, 1320′ is the minimum distance for construction activities that occur within an eagle eye’s view, but it’s reduced to 660′ if it isn’t.

Even so, perhaps the developer could argue that maybe, just this once, this one home can slip through the regulatory cracks without causing much damage. I don’t think so. Because, there are other factors to consider.

What do residents of the lakefront do in their spare time — build docks? Go yachting? Or maybe go fishing, either from the dock or in an unmotorized boat? Or simply enjoy the water and the scenery from the dock or from a kayak or canoe?

What do residents of the lakefront do in their spare time — build docks? Go yachting? Or maybe go fishing, either from the dock or in an unmotorized boat? Or simply enjoy the water and the scenery from the dock or from a kayak or canoe?

These activities are innocent enough. . .as long as you do them while maintaining that 660′ distance buffer from your neighboring eagle’s nest.

Which is impossible unless your home is located well outside of that buffer. And clearly, any home built on this lot would not be.

It is my opinion (and I hope the opinion of the NYS DEC!) that this plot of land should never be approved as a potential home lot, regardless of whether the nest is currently active. Which it is.

It is my opinion (and I hope the opinion of the NYS DEC!) that this plot of land should never be approved as a potential home lot, regardless of whether the nest is currently active. Which it is.

Because if this nest is ever abandoned, it would become a secondary nesting site — and that would require protection.

According to the Plan, “. . .unoccupied or alternate nest sites also need to be protected from long-term disturbance with buffers, and should be considered part of the breeding territory [because] [a]lternate nests are frequently used in subsequent years” (p. 32).

Apparently this developer is fully aware of the protection he must enforce because a protective barrier was dumped here last summer (2019), providing the required 660′ of protection to this eagle nest.

Apparently this developer is fully aware of the protection he must enforce because a protective barrier was dumped here last summer (2019), providing the required 660′ of protection to this eagle nest.

But the rubble has since been removed, and a realtor’s sign has been placed there instead.

Did the NY DEC agree to this? Did they give the developer the green light to go ahead with plans to build on this lot? If so, why? I am awaiting their response to my query.

In the meantime, I don’t understand how, on October 16, 2020 at 8:39 a.m. (which is when I photographed the Keller Williams sign), a realtor actively sought buyers for a property that featured, along with a lakefront view, an active eagle nest.

I don’t understand how the developer AND the realtor (Cecilia Capezzuto for Keller Williams Realty, 585-924-5541) can do this, either morally, legally, or both. Maybe their vision is clouded by dollar signs. . .?

Here is where you can read the New York State Bald Eagle Protection Plan for yourself:

chrome-extension://efaidnbmnnnibpcajpcglclefindmkaj/viewer.html?pdfurl=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.dec.ny.gov%2Fdocs%2Fwildlife_pdf%2Fnybaldeagleplan.pdf&clen=2411363&chunk=true

You can click links to federal regulations, including the Migratory Bird Act, from here, the US Fish & Wildlife Service:

https://www.fws.gov/birds/management/managed-species/eagle-management.php

The Migratory Bird Act also applies to protection of eagle nest sites, except for a brief period where it was “Trumped” in favor of big business. Thankfully, the courts overturned that suspension — and not a moment too soon. One observer wrote, “Had the Trump administration’s policy been in place at the time of the Deepwater Horizon oil spill in 2010, for example, British Petroleum would have avoided paying more than $100 million in fines to support wetland and migratory bird conservation to compensate for more than a million birds the accident was estimated to have killed.” But here, read the opinion for yourself:

https://www.nrdc.org/media/2020/200811-0

Update: Good news from the NYS DEC!

Correspondence with “Jenny” at the Avon office of the NYS DEC tells a little more of the story.

In addition to the Migratory Bird Act, the Lacey Act, and NY State’s own Plan, there are several state DEC regulations that serve to monitor and protect endangered species, including eagles. Obviously, the DEC cannot prevent or regulate the sale of property, including property that host endangered species, “but any development of those lots would likely require permits from NYSDEC, including a Part 182 jurisdictional determination.” Part 182 permits are not handed out lightly; the process is rigorous and the requirements stringent. In fact, Jenny reports that she recalls only two such permits being issued by the state of NY, “both of which involved projects with a public benefit (wastewater treatment for example) rather than just a private or commercial project.” Clearly, if this landowner (or future ones) apply for a permit to build upon this property, “the applicant would have to develop and implement a plan that demonstrates that eagles. . .are better off for them having implemented their project.”

So, it looks like it’s two home lots but only one home that will occupy this property. What a relief!

Many thanks to Jenny for her detailed attention to this issue! I’m glad that people like her work to protect the eagles and other wildlife in Wayne County, NY.

Three babies were raised in this nest during the 2019 breeding season. Let’s hope they (or another pair) will raise three more in 2020!

+ Birds, bridge camera, Caspian Tern, Fish, gear, heron, mirrorless, osprey, Uncategorized

Losing My Fear of ISO

The ISO was only 400 — but the tiny sensor on this bridge camera could not handle it well.

What newbie wouldn’t be scared of ISO?

On one hand, it promises you brighter, better photos. . .

. . .but the other hand takes them away with great big blobs of grain.

Up to now, I simply ignored this third leg of the exposure triangle.

I figured that by keeping the ISO low (200 or below), I wouldn’t have to worry about grain.

But that limited my photos to bright light only, which brought new problems.

Even ISO couldn’t rescue this photo shot in harsh oblique light.

Adjusting the WB and/or using a CPL didn’t really fix things because I am still having a hard time distinguishing harsh light from bright light — until I see the evidence in my photos.

And no matter how I adjusted the white balance, cloudy-day photos were just too dark.

Bummer.

It didn’t take long for me to realize that I needed to face the problem of ISO like a big girl — and the sooner the better.

ISO 800! A number that used to make me shudder in fear!

So, I took a deep breath and jumped in. After scouring the Internet, I found that just because a camera boasts a wide range of ISO doesn’t necessarily mean that it handles it well.

In fact, I found that sensor size is an important factor in ISO performance. So, forget bridge cameras — those tiny, less-than-an-inch sensors just won’t handle ISO well at all!

I decided to set my cameras to Auto ISO but with a limit to just how far it could go.

On my Canon 77d, which has an APS-C sensor, I found I could go as high as 128000 before the graininess became unacceptable.

But on my MFT cameras, I was better off setting the upper limit to 3200.

And the last remaining bridge camera I have — the Panasonic Lumix FZ80 — well, maybe I’ll sell it. It’s a great bright-light camera, but that’s all. For now, though, I think it will just sit on the shelf for a while.

Maybe these settings will change as I improve my technique. . .

Maybe these settings will change as I improve my technique. . .

. . .but for now, this is where they are going to stay

These small changes were quite effective!

I saw IMMEDIATE improvement light-wise.

Autofocus works better, now that there is no low light to struggle through.

Distinct detail is much better to achieve now that autofocus isn’t struggling. No more big, blobby subjects!

See for yourself!

All photos, including those above, were taken with the OM-D EM5iii wearing the Panasonic Lumix Vario OIS 100-300.

Poor little fishie! But froggie is breathing a sigh of relief 😉

ISO 1000! P.S. Nice reflection, no? 😉

Another at ISO 1000. So pleased that I am getting the hang of this!

ISO 640

I love letting the camera worry about the light — except when it clips the highlights!

+ Birds, bridge camera, Butler, NY, egret, Fish, gear, heron, mirrorless, osprey, Uncategorized

A Good Day of Fishing

Touchdown!

Breakfast. . .

. . .lunch. . .

. . .dinner!

Fish. . .

. . .it’s not just for osprey anymore 😉

+ Birds, Butler, NY, eagles, Fish, Geese, heron, insects, osprey, Uncategorized

Do the Dew

Which means you will have to get up early, before dawn even!

Because you can’t do the dew if the sun dries it up before you get there.

But it’s worth the extra effort of getting up and out of the house. The dew lets you see things you might have overlooked in the middle of the day. . .

. . .or which simply does not occur in the heat of the midday sun.

. . .or which simply does not occur in the heat of the midday sun.

The spiders were very, very busy at the marsh located on my very favorite dirt road in Savannah, NY yesterday. They must have captured lots of dinner, because just about every web I saw had insect-size holes in them.

And I saw a lot of webs.

Ewww.

Note to self: Don’t go traipsing around in the brush. . .unless you want to emerge with pantlegs full of sticky spider webs!!!

Animals have to eat. . .and they are more apt to do so early in the morning.

Usually I might see a few herons and maybe some gulls on a sunny (or not-so-sunny) afternoon. . .

Usually I might see a few herons and maybe some gulls on a sunny (or not-so-sunny) afternoon. . .

. . .but early in the morning there are many more of them — plus a few osprey and an eagle or two — plying the water looking for a squirmy breakfast.

I stopped counting herons once I got to 20. They are a good barometer of marsh health — if there are a bunch of herons around, you know there is enough water to support fish. Lots of fish.

And if there are fish, there is plankton, the basis of the marsh food chain.

And if there are fish, there is plankton, the basis of the marsh food chain.

And if there are plankton and fish, there are bound to be frogs and other wiggly aquatic life, turtles (and turtle eggs), plus the furry land animals that like to eat the eggs.

It’s more than a food chain. . .now it’s a food web.

It’s more than a food chain. . .now it’s a food web.

Yay for the marsh!

The frogs are everywhere, too.

Why the herons didn’t snatch up a frog or two I don’t know.

Frogs are easy pickings, much easier than waiting for just the right moment to catch a fish.

But the frogs were pretty much ignored by everyone but me.

But the frogs were pretty much ignored by everyone but me.

I thought they were really cute.

You’d think they would have been quieter, though, what with all those hungry birds flying around.

I mean, why advertise yourself as a meal?

But for the birds it was fish on the menu, and soggy bog plants for everyone else.

More stuff from today’s doin’ the dew:

More specifically, Dragon-Flyday. They were everywhere! I have no idea of their names or what it is that they do, but they are difficult to capture. . .and so pretty! Well, almost. They aren’t as ugly as spiders or as fearsome as wasps. So, “almost pretty” will have to do. But not as pretty as butterflies!

But wait! There’s more!

Wild Onion

I thought it was going to be one of those quiet summer days with wildlife languishing in the sun, too hot to forage or preen, thus limiting my photo ops to flowers and sparkly water.

But it was not meant to be, not if the blackbirds had anything to say.

Turns out they had a lot to say, and do!

Today there were a couple of blackbirds hanging around the Eagle Tree,

and they were feeling kind of frisky.

Frisky enough to torment birds much larger than they are. . .and they’ve set their sights on this eagle, who was minding his own business and thought it was a good idea to rest and maybe snooze for a while.

Not gonna happen, unfortunately!

Blackbirds may be little, but they are feisty. . .feisty enough to torment a bird more times their size!

Blackbirds may be little, but they are feisty. . .feisty enough to torment a bird more times their size!

They dart about so quickly that the eagle has no time to say “Watch out! Here comes a blackbird!”

Because before those words are even out of his mouth (or beak. . .) he’s saying “Which way did it go???”

All the eagle can do is try to scare it away with loud shrieks and squawks.

Maybe it’s gone. . .

But no such luck, it’s only resting!

Oh-oh, look behind you!

No wonder four-and-twenty of them were baked in a pie!

Where’d he go???

That’s it, the eagle has had enough!

Good riddance, you pest!!

Maybe now he can get some rest!

. . .while the rest of us return to the flowers standing as silent testimony to the hot and now-quiet summer afternoon. . .

These photos were all taken with the Olympus EM-5iii and the Panasonic G Vario O.I.S. 100-300 lens.

The JPG processor in this camera, as it is in all Olympus cameras, is outstanding. Unlike the DSLRs, what you see in the viewfinder is what you get in the image. No need for postprocessing at all, unless you want to resize.

And if you are a diehard RAW shooter, Olympus offers in-camera processing for your RAW files as well. Amazing!

Saw this on the June 25 edition of Ugly Hedgehog and just had to share:

The Ugly Hedgehog. Some people love it, some people hate it. You get to make your own decision by checking it out here, https://www.uglyhedgehog.com/newsletter.jsp?np=1

Which explains The Mute Swan Show I witnessed yesterday and why it required a cast of only two.

Which explains The Mute Swan Show I witnessed yesterday and why it required a cast of only two. Ultimately, though, a truce was called.

Ultimately, though, a truce was called.

Recent Comments