Ordered some new-to-me OM-D stuff from B&H, and I’m liking what I am re-discovering. Pairing the OM-D EM1ii with the first version 100-400 lens is all I could afford right now, but it’s a powerful combo, even if it’s almost 10 years old!

Tried it out on some mute swans on Sodus Bay, and it performed well in the harsh light of midday — just a trace of visible blown-out whites.

Then I checked on a nearby eagle nest. This one has been in constant use since 2019, when I began watching it. I was at least 110 yards away, which is the minimal viewing distance prescribed by the Department of Environmental Conservation. That’s longer than a football field, so yeah, this was cropped quite a bit. Happily surprised to see some decently retained sharpness — and good whites!

The real test was with the snow geese. They often rest in this part of north-central New York during the spring migration, as they travel back to their summer breeding ground in the Canadian Arctic. Yikes, I can think of much nicer places to be in the summer, but whatever. . .they’re snow geese and I’m not.

Anyway

I checked out the Savannah mucklands first — that is where I found them last year and the year before, but no go. Despite the recent wet weather, it wasn’t mucky enough to attract much wildlife at all, just a crow or two feasting on leftover corn harvest.

The ex-soybean fields on my favorite-ist dirt road, however, had attracted a huge flock!

Still some harshness to the light, which is more obvious in this cropped photo, but I think the EM-1 handled it okay — well, better than my Nikon does. In hindsight, I should have metered just on the whites. . .and had I paid attention I could have dialed down the exposure compensation, damn. (I will next time, though!!)

Problem, are these all snow geese, or are they Ross’s geese? I’m not skilled enough to tell, and these close-ups are not close enough to reveal the distinguishing features (such as the black “grin patch, bill shape, comparative size, etc). But given the longish neck, I’d say these are typical, run-of-the-mill snow geese. . .still beautiful in their own right and spectacular when congregated in large flocks like this.

Well, when you spook one snow goose, you spook them all. A passing freighter signaled a high alert, and the result was an explosion of snow geese!

I do like the way the way this elderly Olympus gear handled the harsh light despite my newbie approach — something I just can’t seem to do with my expensive, state-of-the-art Nikon equipment. 😦

I so wish I was better at this stuff!

The next day both the snow geese and I had had enough of this yucky light. They were off!

All was not fun and games, though. The light wasn’t all I had to struggle with. . .the mud took its toll. Admission to the Snow Goose Olympics was free, but I had to pay to leave.

I had this singing bluebird and a nice state trooper keeping me company while waiting for the tow truck. Honestly, this pleasant and handsome specimen of New York’s Finest didn’t look more than 12 years old (do they really hire cops that young these days???).

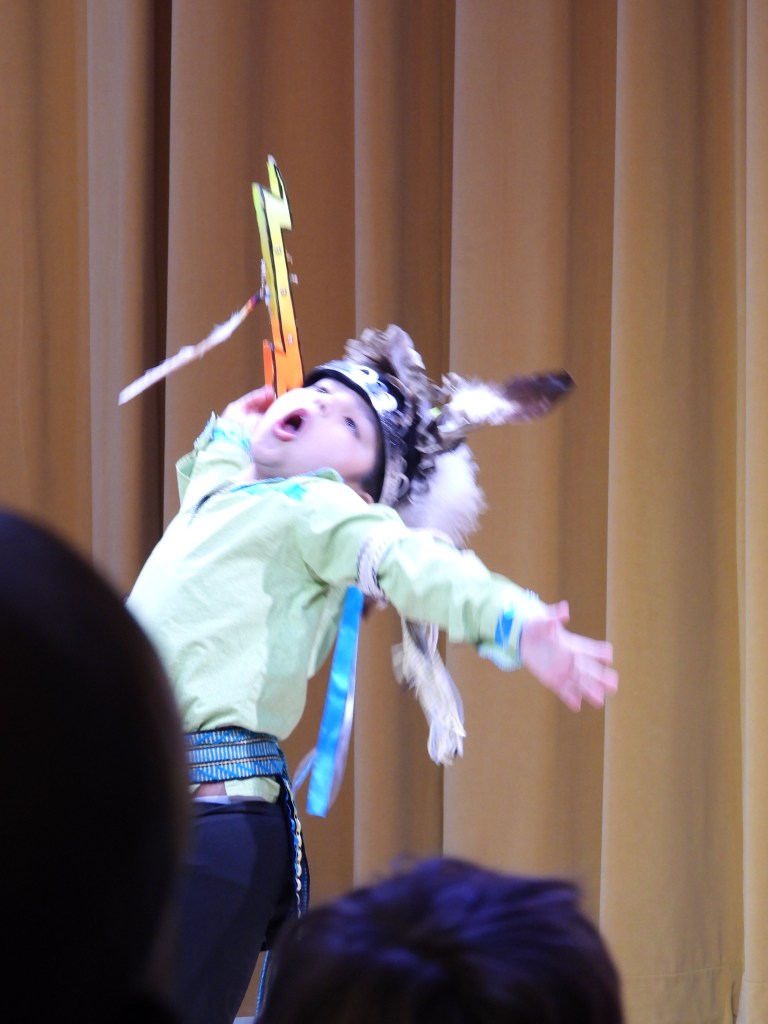

Who remembers the mall! The go-to place for moms, teens, and anyone else wanting to shop, see a movie, meet for coffee, or just hang out. . .and to see Santa!

Video may have killed the radio star, but it was computers — big, small, and handheld — that snuffed out this delightful icon of the pre-millenium and replaced it with one-day-delivery ordered from virtual warehouses, where you may return items with no fee but you will never have the unique experience of an Orange Julius. Or a massage chair.

Or photos with Santa!

This was Marketplace Mall in Henrietta (Rochester) NY, back when I was shooting Olympus. I had a feeling even then that I was chronicling a bit of local color that would soon become history — and I was and it did. After tempting buyers with alternate use ideas and then spending some time in the ghost-mall stage, the 43-year-old Marketplace closed in 2025.

Join in the parade (I’m gonna go grab some Chinese food)

And Christmas songs you love to hear

(Hark the herald angels sing, joy to)

Thoughts of joy and hope and cheer

But mostly shopping, shopping, shopping!

Wrap them up and pray for snow

Hope you enjoyed this walk down Memory Lane!

(published February 12, 2026)

Even back then, a bridge camera was not my first choice. I had heard all about the limitations of their tiny sensors, especially when it came to dynamic range and dark, cloudy days. Besides, I was perfectly happy with the Canon 77d. I couldn’t afford Canon’s new flagship, the wildly popular 90d, but lucky for me, they had stuffed most of the 90d technology into a cheap plastic body and called it the 77d, which made things more affordable for us poor folk. Anyway, I got some good stuff from it, especially when paired with the 100-400 f/4.5 – 5.6 USM.

But then one day in July an off-duty sheriff decided that the speed limit in the redneck town of Sodus was way too slow for him. While passing the offending vehicle, Sheriff Joe plowed head-on into me, toppling my car into a ditch and sending camera, lens, tripod, lunch, and me flying. I survived. The electronics didn’t. But after some quiet convincing by my barracuda lawyer, Sheriff Joe reimbursed me for everything (except the lunch) and as a courtesy threw in enough extra cash to pay off my mortgage.

Well, my lawyer wasn’t really a barracuda. He was just a nice, older man with two witnesses, one who wondered if the sheriff was trying to qualify for the Indy 500 and the other who wasn’t surprised because the sheriff had gone “flying” past him moments earlier.

So, I made do with a series of cheap used cameras, including that wonderful gifted gray-market Canon 1100d that I absolutely adored. Once discharged from the ICU, I collected a pocketful of Sheriff Joe’s cash and stopped at the bank before heading to Best Buy. I had been eyeing Sony’s new mirrorless, the A6000, for the past few months.

I liked it. It was a nice, lightweight camera with an APS-C sensor, just a little larger than what I would soon find in Olympus gear. I did get some good results, but the build quality was atrocious. It was serviced three times in six months. After the last repair, I traded it in and started looking at bridge cameras.

Why bridge cameras? Because I don’t know. I tried a few of them before I settled on the Sony bridge.

I hated Nikon’s p1000. It had an astonishing focal length — more like a small telescope than a camera — but it was essentially unusable. At full extension the center of gravity moved away from the camera body and landed somewhere in the middle of the extended lens barrel, where you can’t place a tripod collar. This made it impossible to mount unless the tripod was counterbalanced with a bag full of rocks. Even so, the camera was so out of balance that it shook terribly, even when using a remote. And once you managed the set-up you had to shoot real quick, because the lens retraction time was always-always-always less than the time it took to properly compose and expose the shot. I *could* get decent shots — but only if I didn’t extend the lens beyond 518mm.

C’mon now, what good is having a camera with an amazing focal length if you can use only half of it?

Beautiful downtown Clyde, NY — don’t blink, or you’ll miss it.

I was still avoiding the world of raw but knew I would eventually succumb, so my next choice was the Sony RX10iv. The photofolks still frowned, but who cares, it has a nice, lightweight build, a 1″ sensor, and yeah, Sony color science! And it didn’t fall apart like the a6000 did. In fact, I still have it today along with some macro lenses I picked up while visiting in San Francisco.

Go Orange!

Which bring us to Part II, Cameras I Have Known: Olympus.

(published February 6, 2026)

I started with the EM10 beginning in late 2019, during my early days. Although this camera had raw capabilities, I didn’t bother with raw files back then. The jpgs it produced were. . .not bad, really. Besides, I dreaded postprocessing, which I knew nothing about. Besides, it was something (I thought) jpgs didn’t need, not when my Olympus did most of the work for me.

By 2021 I had progressed from the EM-10 to an EM5, then to an EM1iii and finally to the pièce de résistance, the EM1x (before JIP rebranded OM Systems as OM Digital Solutions).

I loved the EM1x the best, but in truth I loved anything that fell out of my Olympus cameras — even when it was just a jpg. Especially when it was just a jpg — because the Olympus color science is quite remarkable, maybe even better than Sony. Noise? Hardly any! Plus, the gear was light, easy to handle. It had IBIS to die for. — even me, a raw newb, could handhold at very slow shutter speed and get nice, clean, silky water. Robin Wong, an Olympus ambassador at the time, was my constant YouTube companion, showing me the capabilities of the Olympus EM line and explaining how M4/3 got such a bad rap.

I believed every word he said. And now that I have a little more experience with the Big Three, I still believe every word he said.

Those early days were full of innocent fun. If it stayed still, I shot it. If the light sucked, a stick blocked the subject, or an animal posed for butt-shots only — I shot that, too. I was in awe of these curious technical gadgets that produced such wonder, and I was thrilled when my photos resulted in a decent and recognizable subject.

These really aren’t bad photos! But I wanted to improve, so I joined the Rochester NY Nature Photography Meet-Up group. . .which is where *real* photographers gathered once a month to talk to each other. I did a whole lot of listening but wasn’t really allowed to talk much. I did learn a few things, but the biggest lesson was how to scoff at M4/3rds products, none of which were tolerated by these real photographers. They shook their heads, begged me to upgrade to something else, and predicted I would never amount to much unless I did.

It took a while to realize that this barrage of criticism — some of it deserved, and some not-so-much — would continue as long as I clung to Olympus Systems. That’s when I left the group — it was easier to let go of a bunch of egotistical grumpy old men (and a few egotistical grumpy old women) than it was to let go of my precious Olympus cameras and lenses.

In retrospect, the likely problem was that none of them had any time or patience for a newb.

I suppose they would probably all be very happy to know that, on the half-trusted advice from a short-term mentor, I eventually traded it all in for some Nikon stuff (on a very sad and gloomy day back in 2022. . .).

Now that I have a little experience, I am seriously thinking about getting reacquainted with Olympus, perhaps an EM1ii paired with that glorious 100-400 lens. Older stuff, to be sure, but imagine what they can do! now that I know their capabilities.

(published February 6, 2026)

It’s winter out here in the western/northern Finger Lakes region of New York, which means there’s not much going on.

So, I spent a few minutes today looking at all my blog posts. . .okay, more like a couple of hours. Some of my photos downright embarrass me! A few others are so good I can’t believe they’re mine. Most, though, are mediocre (according to REAL photographers), but who cares, I see pleasure and improvement over the years, and that is very satisfying. 🙂

As I ponder, I regret some of the gear choices I have made. I started with some inexpensive Canon gear and then downsized (by necessity, thanks to a rogue sheriff who totaled my camera and my car) to a couple of older, gray-market gifts. I ended up with a seven-year-old, inexpensive, gifted gray-market Canon. . .hey, don’t let anyone tell you how bad these products are! I got some pretty good shots, especially from my 1100d, before they all passed, one by one, into that 18% grey stratosphere far above, the final resting place of all good cameras once their time on earth is done.

I fooled around with a few different brands for a while, trying to find the one with the best results. As I look back, I think I miss my Olympic gear the most. Loved the color science, the IBIS, the lenses, the weight (or lack thereof), but was convinced by a former mentor to ditch it — well, I ended up ditching him, but not before selling all my Olympus gear (wahhh) and investing in Nikon . . .but I might try to find some lightly used Olympic stuff, to see if I reallyreallyREALLY like it or if I’m just being nostalgic.

These photos could use some improvements, I know, but considering that they all fell out of the camera as untouched jpgs, they really aren’t that bad. What I find really curious, though, is the noise factor — none were edited for noise (or anything else other than an occasional crop), but noise doesn’t to be much of a problem with the small-sensor Olympus and Panasonics. Even my Sony Rx10iv doesn’t produce much noise, and that sensor is downright tiny. Huh?

Anyway, in 2023 I began shooting with the Nikon d500 and d800 along with a 200-500 lens. Later on I added a Z9 and a 500 PF prime with an FTZ adapter and 1.4 extender (that was back when I had some leftover sheriff money). Under the tutelage of the aforesaid mentor, I learned how to shoot raw and to make simple corrective edits with ACR. Even so, I was still disappointed with most of my photos, and a good number were best treated not by ACR but by <delete>. I didn’t need anyone to show me how to use THAT.

Nonetheless, I remain determined to improve my technique — that’s an achievable goal, right? even for a short, round, opinionated old lady.

So, once the mentor had outlived his usefulness, I graduated to the self-education available on You-Tube. Much cheaper!

However, I really didn’t get significantly better photos despite wasting a lot of time (and brain cells) worshipping YouTube’s guru-du-jour. Oh, these guys are well known among Nikon and Canon crowds, so it’s really no secret who they are. They make a lot of noise and a lot of money enthusiastically preaching about photography done right (which translates to “done my way”), but all I learned from them were some specialty terms and how to select (what I thought were) the best lessons from all the conflicting advice. And I still returned from the field with a camera full of soft, flat photos.\

Ewwwww.

But then I learned something astonishing. It struck me one day like a snowball thrown by a giggling, pimply-faced 14-year-old: YouTube lessons work best when unlearned. I discovered this after finding a Facebook group called Nikon Teaching Photography. The admin, Bob Scola, has a large following and a stellar online video library hosted on EyeSo100 explaining all things Nikon. You can check it out here:

https://www.eyeso100.com/spaces/10626684/content

and for $100 a year (or $10 monthly payments for us poor folks) it, too, can all be yours. (Actually, I’ve wasted more money at McDonald’s, where I could sit undisturbed, shaking my head while previewing and deleting the day’s photos. . .)

My first Bob Scola lesson — a mortal sin in the eyes of the YT deities — was removing “back button focus” (Holy Skepticism, Batman!). Because, really — what does it accomplish, other than move the shutter button functions elsewhere? Actually, it does exactly what The Temptations told us back in 1969 when they sang about “war, humph, good God, y’all, what is it good for” (answer: “absolutely nuthin! (say it again). . .). But I suppose it can be quite entertaining if rearranging camera button functions amuses you — and if it does, congratulations! You’re in a cult!

And thus began my foray into real photography education.

(HINT: If you do join Nikon Teaching Photography, don’t even try to defend BBF. Just go watch the EyeSo100 video, which clearly debunks all the hype, and if that doesn’t help you then go back to YouTube. Because just a few days ago someone got blocked for ignoring the video and arguing on its behalf, even though he was very polite about it, just sayin.)

I found Bob after an outing where I had captured a stunning composition of two young foxes playing on some railroad tracks. . .until an oncoming mile-long freighter sent us all running. Once safely seated in the car, I eagerly opened <preview> — and found that every single photo was just awful. . .I was horrified! Every, Single. One. Oh, they looked great on the microscopic camera screen, but at 100% they were unbelievably bad — soft focus, poor exposure, glaring white areas — despite completing my You-Tube checklist:

- meter and exposure-compensate for good exposure

- use “telephoto feet” to avoid direct harsh light

- capture adorable images using the Rule of Thirds

- steady the camera, lens, and photographer against the side of the car, using VR to prevent movement and camera shake

- spot-meter (actually, I used highlight-metering) the white areas to avoid blow-out

- use combination of a wide aperture (to get the best bokeh) and a fast shutter (to lessen harsh light and capture any unexpected action)

. . .and none of it worked. These photos punched me in the gut every time I looked at them.

Desperate to salvage at least one of them (I felt the composition was that good), I sought advice from a “beginner’s” FB group that I had found (where else but) on YouTube.

Big mistake. It was a public group whose resident exclusionary experts offered unintelligible advice gathered from the most esoteric parts of the 300-page Nikon manual — all of which they knew by heart and performed on a regular basis, which is why they were all photography oracles. But in truth what they said boiled down to “sucks to be you but not to be me.” All I got from them was embarrassed, especially when the admin featured my horrendous photo AND MY NAME! (without my permission) on his world-wide YouTube channel as proof that some photographers are so lousy they shouldn’t even waste their time. Or his.

Speaking of wasting time, he wondered out loud why I didn’t correct the slightly-off horizon. Dude, what for? Why would I bother with a one-degree horizon correction on a photo that clearly could not be salvaged?

(I’d tell you HIS name, but I hate him, so all I will say is that, should you wish to be insulted (free of charge!), you can find him on YT and FB as “Photography Explained.” I would propose a more appropriate title, something along the line of “Photography Explained by Arrogant Dummies,” but what do I know.)

Anyway,

after suffering a severe existential meltdown (complete with tears), I blocked the arrogant Professor Explained and his equally arrogant (and nasty) FB disciples. I then contemplated selling all my gear at bargain prices — why not, I was hopeless! — but after a couple of weeks I had recovered enough composure to try just. one. more. time — and that’s when I found Bob Scola. No shame! No bragging! No snarky comments! No swaggering self-promotion! Just good, solid, workable advice explained in a way that even *I* can understand.

And it really helped! I found features on my cameras that I never knew existed, which allowed me to better utilize my gear. I learned new and effective techniques that were easily replicated and produced the predicted results. But most of all, I regained my confidence, which allowed me to remand Photography Explained to a level so low that they had to look up to see the electronic basement — a place where all public groups, world-wide YT channels, and their pompous keyboard elitists are free to spend their days impressing their friends and confounding their enemies and spend their nights — well, I don’t want to know what they spend their nights doing.

So, I decided to test my new knowledge and took a ride out to my favorite-ist dirt road in Savannah, NY, where I had originally found the foxes but now hoped to find a few hardy winter birds. Maybe my photos won’t be perfect, but at least now I will understand why and will be able to take the necessary steps toward improvement.

The first lifeform I found was this inquisitive squirrel. A little soft, but better soft than no shot at all (the tree bark, though, is nice and sharp — I mean, it’s not like I didn’t have the focus box squarely on his eye, but on the z9 it has a way of jumping around at the last nanosecond, especially if there is more than one plane of focus).

There were sparrows galore, all feasting on the dirt-road grit. Of course they scattered, despite my sly attempts to keep my distance.

In fact, I was so intent on (visually) capturing a few more tree sparrows that I nearly missed this guy, watching the show from his (her?) perch high above the fray.

I waited about 30 minutes for him to take off, but no go. He did, however, have an itch. Or maybe he was looking for his keys:

Eh, the most exciting thing I could catch was a sudden spook, which caused a rapid spin-around that almost dislodged the poor thing:

The Merlin app thought it heard a screech owl, so I was off to find it. No luck, but I did find a heap of trumpeter swans, a bunch of gulls, and a variety of geese hanging out in the mucklands.

Savannah’s mucklands are a unique geophysical attribute resulting from Seneca River overflows, which happen when even a hint of of wet weather threatens to descend (the water table is quite high in this area and the river hasn’t been dredged for decades). The town is proud of this feature — they even have a road named Muckland Road (…as well as another named simply “No. 39.” Gotta luv beautiful downtown Savannah!). During migrations the mucklands provide a resting place for ducks, geese (sometimes even a flock or two of snow geese), and swans. They are safe from hunters here, because the mucklands are also farmlands whose harvest litter attracts foraging birds and other animals; therefore, hunting is prohibited by local, state, and federal regulations.

The crows were not welcome in the mucklands, but they amused themselves by annoying each other while foraging in the adjacent icy marsh.

Off to the B&H site to check out some Olympus prices!

(published January 17, 2026)

I had a choice this year. I could spend Thanksgiving with my camera at the soggy bog.

Or I could force my way into the ubiquitous family dinner, which would, of course, require an additional wardrobe purchase.

(Is this a trick question?)

The choice was a no-brainer.

Armed with my camera, lenses, and a lunch consisting of a Pink Lady apple, a piece of homemade cheesecake, and a bottle of Ice carbonated beverage, I headed towards the soggy bog.

And look what I found on the way!

Upon arriving at the bog, I found that *someone* had just had their dinner. . .

. . .and by now were probably lounging at home, watching the Eagles game

This furry friend was still at the table.

Others were resting after a long search for their slippery, wiggly holiday dinner:

There were LOTS of gulls here today.

There were also lots of Canada geese — what would western NY be without flocks of Canada geese?

Some of the residents were just hanging around, keeping an eye on things (there are actually two of these great blue herons who chose to remain here rather than migrate south.

Today I decided to travel down a nearby wooded dirt road leading to some soybean fields. Glad I did, because look what I found!

A hungry downy woodpecker tapping the tree for insects

A few onlookers. . .

The ducks, however, had had enough. and decided to get a head start on the incoming snowstorm:

Photographers generally avoid “bird on a stick” photos, considering them dull and uninteresting. They would never win a prize at a contest.

There is absolutely no hope for me. None of these photos would win a prize because none of them exhibit the technical quality and artistic talent required by a contest winner — well, the beavers had some talent, but they’re not photographers so they don’t count. In any event, the mundanity I managed to capture with my camera is more valuable to me than an honorable mention in some contest. It serves as a pleasant reminder of a Thanksgiving holiday spent in solitude and quiet reflection without the self-doubt, anxiety, and stress of spending it with a bunch of squabbling, hypercritical family members.

I hope their holiday went as well as mine.

(published November 30, 2025)

Is THIS why the managers at Montezuma National Wildlife Refuge drain the marshes every spring? And allow the resultant mudflats to lie fallow over the summer? And then flood them in late summer/early fall? To lure large quantities of ducks to the refuge with acres of duck-friendly vegetation? Just in time for fall migration?

Well, yes, that is what they tell us.

But what they don’t tell us is that fall migration coincides nicely with New York’s duck-hunting season. Because we aren’t supposed to know that they lure both ducks and duck hunters to the refuge with this clever plan.

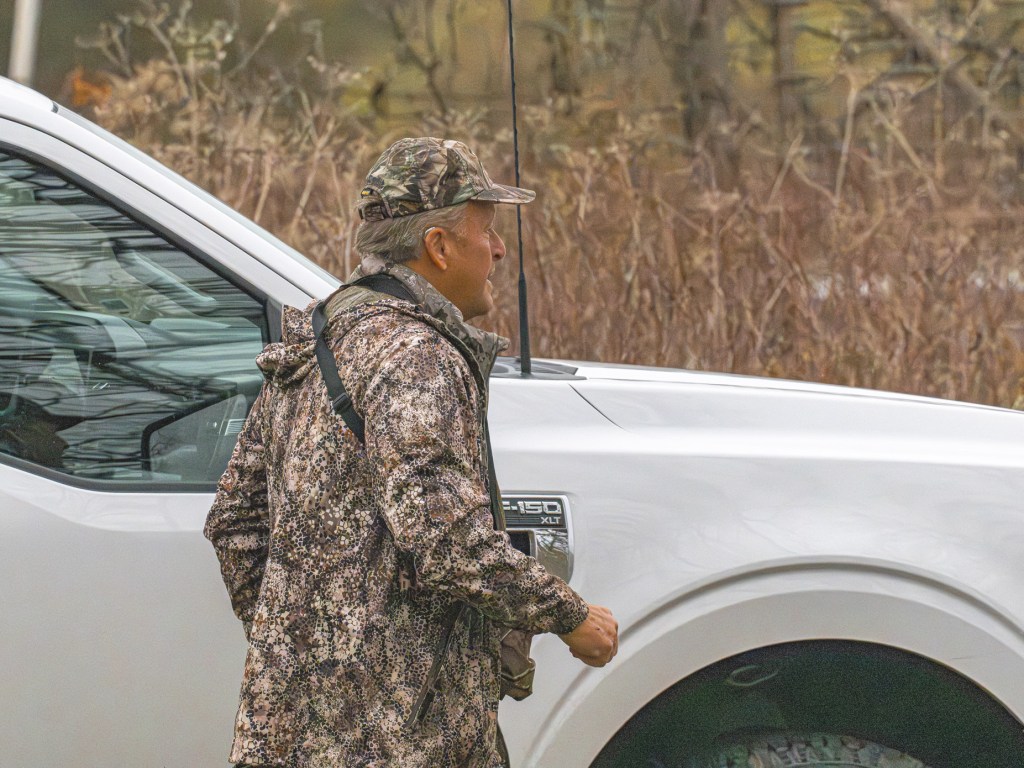

This guy was parked on Wildlife Drive on Sunday, November 9, 2025, even though the Drive remains open to the public until December 1. It is my understanding that public access is why duck hunting is never allowed at the marshes bordering Wildlife Drive. . .but apparently I understand wrong. Evidently it’s allowed as long as no one from the Refuge staff is looking.

This entire debacle is unnecessary. While drainage does “refresh the marsh,” such refreshment is required only on those occasions when the regional weather cycle fails to provide natural drought –which occasionally happens during the more-or-less 5-7 year cycle. But even on those rare occasions when nature fails and the water table must be lowered, it needn’t be downdrained to mudflats, nor should it be drained more frequently than once within the 5-7 year cycle. In fact, too-frequent drainage, whether induced or natural, hastens the degradation of emergent wetlands, which will convert to a trees-and-shrubs environment in about 10 years, sometimes in as little as 2-3 — check elsewhere on this blog where I’ve written about the current conditions of Knox-Marcellus Marsh, the result of a prior failed “marsh improvement” endeavor conducted jointly by MNWR and Ducks Unlimited (don’t believe me? it’s engraved on a brass plaque stuck to the boulder in the parking area).

I suspect that this truck and its owner are evidence that the varied explanations MNWR offers for its periodic destruction of the food web, necessary to maintain the exclusionary waterfowl population they desire, are simply “alternate facts” designed to convince us that killing off the resident water dwellers and driving away dependent wildlife each (or nearly each) spring serves some kind of lofty environmental purpose. . .and that hunting is a byproduct of negligible importance.

It doesn’t (when it’s overused) and it isn’t (especially if you’re a duck).

This year’s “simulated drought” coincided with the natural one that affected central New York, so the refill, then, was much shallower than expected. A good thing for ducks, because they are less of a target when hidden in the proliferative unsubmerged vegetation. . .but that didn’t stop this guy. He was going to duck-hunt anyway.

According to one MNWR rep I recently spoke to, this year’s drainage was also intended to control invasive species, specifically invasive phragmites (a type of opportunistic reed grass). That, too, was an epic fail as far as Eaton Marsh is concerned — search elsewhere on this blog to see the photos.

Anyway, this year’s politics worked against the quid pro quo expected from MNWR by Ducks Unlimited. Mike (“The Little”) Johnson’s House shutdown and the bumbling, ineffective, and corrupt government that produced it inadvertently protected the wetlands from further harm by keeping marsh managers unpaid and therefore away from the dike controls. . .a small and short-lived benefit of the BBB <sigh>.

Their return won’t stop me, though, from trying to enjoy the little bits of wildlife that survived the destructive and disastrous summer of 2025:

Rarely do we find a feral muscovy duck in the wetlands, but I found one foraging disturbance-free at the Sandhill Crane Unit, where marsh managers are absent and water levels remain “unrefreshed.” In fact, even during this very dry summer, the water remained at wildlife-sustainable levels.

It was there until the hunters arrived, that is.

FWIW, hunting IS permitted on the PRIVATE LAND bordering the Sandhill Crane Unit, but it is NOT permitted on SCU land or in its marsh. Both the land and the marsh belong to the MNWR complex and are managed (and apparently ignored, thank goodness) by the cooperative efforts of the New York Department of Environmental Protection and the US Fish and Wildlife Service. So, if they won’t enforce their own regulations, I found a way to do it for them. Since sound carries easily over water, I had some good fun intermittently and unexpectedly sounding the horn. . .I did this several times while driving up and down the access road until either the ducks or the hunters scattered.

It’s one thing to hunt ducks — but it’s unnecessarily cruel to hunt ducks at a refuge. . .although trying to lure them with a whirl-a-gig painted like a Canada goose wasn’t very effective (that part was actually kinda funny).

In any event, wildlife aren’t stupid. They know there are safer habitats elsewhere.

By the way, INWR itself doesn’t financially partner with Ducks Unlimited. Maybe that’s why they don’t bother to artificially increase their duck population. By not tampering with the natural food web, INWR attracts the full gamut of wildlife, not just ducks — something that apparently conflicts with the MNWR business plan.

Hoping for better days next spring! Unfortunately, we’re stuck with the “magnificent muck duck hunts” sponsored by Ducks Unlimited until waterfowl season ends.

(published November 9, 2025)

+ bridge camera, Coots, Crane, Ducks, eagles, Fish, gear, Geese, grebes, heron, Migration, mirrorless, Montezuma, muskrat, natural, swans, Uncategorized

Carnage Continued: Montezuma National Wildlife…Place

Apparently little has changed since 2017, when the Montezuma National Wildlife Refuge thought it might be a good idea to devote each spring and summer to cultivating vegetation, hoping to attract large numbers of waterfowl to the refuge during the fall migration. Sounds good on paper perhaps, but in practice this creates a wildlife nightmare. In order to provide sufficient acreage for their duck-food garden, the wetlands are drained down to mudflats, killing off the water-dwelling fish, amphibians, and reptiles in the process. With the aquatic food chain destroyed, the food web collapses, and the resident wildlife that depend on it are driven away. The number of ducks lured to the refuge by this tactic will vary each year, but those that do show up arrive just in time for New York’s duck-hunting season.

I wrote about this back in 2021, and despite the uproar it created MNWR continues maintaining their duck-food garden. However, now they forewarn us via the US Fish and Wildlife Service website. The drawdown that’s coming, we are told, “refreshes the marsh.” It’s done once “every 5-7 years” in order to “maintain habitat for migratory birds and other wildlife” No wildlife are harmed because “[w]e only drain one large pool at a time.” Finally, “[w]hile it may inconvenience wildlife observation opportunities” and collapse the food web, the animals are never really in danger because they “will find suitable habitat” elsewhere.

Personal observation pokes holes in this story. In the 7-year period between 2018 and 2025, there have been several drawdowns, none of which has “maintained” any habitats — if they did, there would be no “lost observation opportunities,” no food web destruction that kills some wildlife and forces others to flee, no carrion littering the landscape, no contradictory photos (see below), and there would be no cause for this essay.

And, while they claim to limit drawdowns to “one large pool at a time,” they don’t acknowledge that there is only ONE “large pool” to drain. How do you sequentially drain a single pool?

Apparently, someone over there lies like a Republican press secretary. . .but in true press secretary fashion, logic is dismissed as a momentary unpleasantness that disappears with a few harsh words and a vigorous denial.

Anyway, I respectfully call bullshit on that entire waste of bandwidth.

I began visiting Montezuma in 2017, when there was appreciable water in all the pools. Not so in 2018, when I witnessed my first (and likely their eleventy-seventh) drainage. MNWR’s scheduled 5-7 year drawdown cycle corresponds to NY’s natural drought cycle. This makes marsh drainage (including complete drawdowns) unnecessary unless nature fails to produce drought within that 5-7 year cycle. This present (2025) drawdown — taking place in the middle of a natural drought — and is disturbing. The fact that MNWR has induced additional droughts within that same 5-7 year schedule is even more disturbing.

Whenever I ask about the dried-up marshes, the explanations vary from “to simulate drought” (yearly?) to “to control the invasive carp” (which are controlled by a canal gate) to “the canal gate needs repair” (this one I’ll give them — once) and finally “we need vegetation to feed the ducks” (ding ding ding, we have a winner, folks!). Just a couple of weeks ago, a USFWS employee added another reason, “to control the phrag[mites] grass.” A curious response, since lowering the water table to zero creates acres of wet and wasted mudflats upon which phragmites thrive.

In fact, the current standard of control is outlined in A Guide to the Control and Management of Invasive Phragmites ([Michigan] Department of Environment, Great Lakes, and Energy, 2014). Since P. australis is highly invasive and difficult to control, wetlands managers are advised to avoid practices that encourage its growth:

“Traditional moist soil management, in which impoundments are drawn down to produce mud flats in early summer, may encourage growth of Phragmites.”

Well, duh. Furthermore,

“If Phragmites is on-site or in the surrounding landscape, managers should use caution when timing drawdowns. Drawdowns should be conducted in late summer (late July) to maintain and promote native vegetation and to avoid reestablishment of Phragmites.“

(. . .even if it messes with the duck food cycle, just sayin.)

The worst of these drawdowns, in my opinion, occurred in 2021, when the levels were reduced so rapidly that the water-dwellers died in a very short period of time. Rotting carcasses extended across Wildlife Drive, and the stench was unbearable. That’s when I decided to research which one of these answers, if any, were valid and then write up my findings (published elsewhere on this blog).

In case anyone who denies the frequency of the drawdowns is also bad at math, the 4-year interval between 2021 and 2025 falls short of the “5-7 year” schedule MNWR claims to maintain, and this isn’t even counting the intervening drawdowns conducted between 2018 and 2025.

I don’t understand the how the managers “refresh” the pools “one at a time,” because they don’t. The dike system that controls water levels is located in the single large (main) pool. Whether by necessity or design, when the main pool dries up, so do the smaller pools and feeder ditches located along the Drive. There is no water anywhere. The fish food chain and the web it sustains collapse like a house of cards. There is no longer a habitat to maintain and no wildlife to maintain it for. The destruction covers the entire 3.7-mile stretch of Wildlife Drive, clearly obvious to anyone driving along the roadway.

Besides, it would be nice if they DID drain only “one [large] pool at a time,” because dedicating that single dried-up pool to duck food farming would keep the other, smaller ones filled with water to thus support the fish-eaters and waders.

But, I digress.

Anyway, don’t just take my word for it. Take a ride along the loop and see for yourself.

“Well,” you may ask, “what about the other side? Isn’t there water there?” Yes, there is. The Seneca Canal runs for the entire north/south length of the Drive. It attracts boaters and fishermen along with an occasional cormorant, a few eagles and osprey, and a kingfisher or two, but rarely a great blue heron or egret, and never ducks, yellowlegs, or other small birds. That’s because its relatively deep-water habitat and negligible shoreline are unsuitable for waders, divers, dabblers, and other wet-edge feeders that by instinct thrive in shallow-water marshes.

I took these photos (unless credited elsewhere) to show what happens when people in charge of managing a refuge don’t know what the word means, which the local USFWS defines as “maintenance of ] diverse habitats [that] give food, shelter, water and space to many of Central New York’s wildlife species.” However, this purpose is meaningless at MNWR as they periodically maintain a duck food garden in the mud, proving beyond doubt that when any one part of a food web is decimated, the rest of it is destroyed as well. Even though the USFWS asserts that “[w]ildlife on all National Wildlife Refuges comes first,” what they really mean is all National Wildlife Refuges except this one.

This begs two questions: 1) What is so important about attracting a hyperpopulation of ducks to the refuge each fall? and 2) How does this justify the destruction of the very habitats MNWR is tasked with preserving? Montezuma personnel have yet to acknowledge my questions, much less answer them. (“Simulating drought” is not an answer, it’s an overworked excuse).

I recently spoke to Logan Sauer, Resident Park Ranger and Visitor Services Manager at another NWR. The Iroquois National Wildlife Refuge faces the same problems that Montezuma faces — reclaiming and maintaining marshes from farmlands lying within the Atlantic Flyway. They also share the same environmental, geographical, and weather conditions, so one might expect their maintenance practices to overlap.

They don’t.

Mr. Sauer spent some time explaining the INWR marsh maintenance policy as essentially dictated by both established and predictive weather patterns. This is how the standard 5-7-year water-lowering cycle was devised (unlike the “duck food cycle,” which seems to occur whenever MNWR wants it to). The water tables at both refuges are controlled by a dike system that permits intervention at will. However (and this is important), it is done at Iroquois only when nature fails to self-correct. To date, partial drawdowns have been required on occasion but never annually, and when they do occur some water level is maintained. And they do drain only “one large pool at a time.”

What he is saying is that INWR maintains their wetlands according to the established standard of care, unlike MNWR, which manipulates their wetlands while overusing the established standard of care to produce a duck-hunter’s paradise each fall.

Of note, duck hunting is also permitted at INWR — but unlike MNWR, they do not partner with a self-interested donor, so there is no expectation of quid pro quo. None of INWR’s wetlands are groomed to produce duck-friendly vegetation to the exclusion of other resident wildlife. The ducks that are attracted to Iroquois wetlands are not artificially baited and thus are not exploited by either hunters, visitors, or refuge staff. That’s because the goal, according to Mr. Sauer, is to “maintain the diversity of habitats naturally present” in the wetlands (emphasis mine).

(Not discussed were the possible benefits of allowing the water table to regulate naturally once these farmlands are reclaimed, https://conservationevidence.com/actions/3198 . There just wasn’t enough time to do so.)

Sounds reasonable, doesn’t it? Except when it falls from the face (or the keyboard) of an MNWR rep. Then it sounds like bullshit.

Mr. Sauer was unaware of and unfamiliar with the practices I’ve observed at MNWR. I didn’t tell him where I observed them, because when I broached the subject the look on his face was a mixture of horror and confusion.

While Iroquois and Montezuma do share problems, they clearly do not share philosophies. I suspect that’s because MNWR has something that INWR doesn’t — a financial partnership with the nation’s largest, most influential, and best-known duck hunting organization, Ducks Unlimited.

There is no reason, other than quid pro quo, for MNWR to periodically abandon their mission of protecting and preserving diversity of wildlife and their habitats in favor of a creating one exclusively for ducks. Waterfowl — ducks, geese, swans, rails, and coots — are neither threatened nor endangered, and there is no shortage of regional feeding/rest areas on the flyway. In fact, the Montezuma refuge lies adjacent to the extensive Seneca Lake marshes which, to my knowledge, are never drained or “refreshed” but manage to attract ducks nonetheless. There is absolutely no need for Montezuma to continue (over)using any duck-luring tactics — unless, of course, they wish to reward DU for its financial and in-kind contributions by providing a less-restricted and more populated duck-hunting experience than what is offered at the state-controlled Seneca Lake.

So, why do they do it? Why do they consistently violate public trust by performing the wildlife equivalent of mass murder, just to please a few duck hunters? Oh, that’s an easy one. They do it because they can.

According to federal and state regulations as well as USFWS guidelines (yes, the same USFWS that co-manages MNWR), individual hunters are subject to fines and/or license suspension should they be caught baiting wildlife. That’s why hunting is prohibited on “manipulated” (planted and harvested) land as long as bait — grain or seed — remains on the ground (USFWS regulations specifically mention cornfields, since the post harvest litter could — and does — attract foraging wildlife). That’s also why DU (and other) hunters avoid Savannah’s agricultural mucklands bordering the Seneca River. Instead, they hold their “magnificent muck duck hunts” (their words, not mine) just a few miles away at MNWR, whose endeavors ensure expansive, huntable mucklands of their own (something that isn’t philosophically possible at INWR — you know, that whole “diversity of wildlife habitats” thing).

And it’s all very legal. One would think that MNWR’s muddy duck-food garden would guarantee a hunt-free environment, no? Because the USFWS regulates “wildlife food plots” as carefully as they do farmland, right? WRONG, because they’ve stuck this exemption right in the middle of all the restrictions and prohibitions listed in their guidelines:

“If you restore and manage wetlands as habitat for waterfowl and other migratory birds, you can manipulate the natural vegetation in these areas and make them available for hunting.”

The Migratory Bird Treaty Act (16 U.S.C. §§ 703–712) protects migratory birds, including migratory ducks, from being killed, sold, hunted, taken, or captured. Even collecting cast-off feathers is illegal without a permit — but it’s OK to shoot them as long as you do it at MNWR.

Kind of skews the entire meaning of the word “refuge,” doesn’t it, luring animals to rest and feed, only to sneak up, shoot them, and throw them in a boat. Having attracted them to a refuge. With bait.

“BAM! Right between the eyes!” — Marisa Tomei (My Cousin Vinny, 1992).

I don’t financially subsidize MNWR and I rarely visit there anymore since I don’t much enjoy witnessing the effects of poor wetlands management. Pleasanter opportunities await elsewhere, especially along the backroads. These wetlands are smaller and subject to the whims of weather but never require “refreshment” beyond that supplied by nature — and even when nature fails they manage to attract all sorts of wildlife, including ducks. Who knew!

I must confess, though. Recently I myself was lured to MNWR by an intriguing Facebook photo. It showed two cars stopped on the Drive and an MNWR representative scolding at least one of the drivers. Apparently someone had lingered beyond the allotted 5 minutes and/or was observed getting out of their car in an effort to photograph the resident owl family. Such conduct stresses the birds and “ruins it for everybody,” according to the post. Laughed out loud at that one, because said employee was neither confined to a car nor constrained to a 5-minute-or-less tirade while her colleague dutifully and digitally preserved the egregious visitor conduct as some sort of evidence.

Besides, how stressed do they think the birds get when MNWR employees watch animals die as they intentionally collapse the food web by draining the marshes? Asking for a friend.

FWIW, I knew about this owl but had avoided looking for it because it would be too stressful — for me (I don’t do well with glaring looks and sanctimonious verbal assaults). Besides, I already have (stress-free) photos of the great horned owl family that nested at Sterling Nature Center a couple of years ago. At Braddock Bay, where staff and volunteers assist visitors with advice and guided hikes, I photo’d some saw-whets napping high up in a pine tree. (They don’t call it Owl Woods for nothing!) BTW, Hawk Creek routinely offers educational programs and, for a small fee, photo walks as part of their outreach.

I mentioned all this in my reply to the FB post, further noting that MNWR’s owl chose to nest proximate to Wildlife Drive because her maternal instincts deemed it safe to do so despite the moderate traffic and occasional photographer, neither of which has caused her to abandon her family or move it elsewhere. So, I wonder just who is stressed by such flagrant disobedience — is it the owl or the rep?

In any event, it took about 10 minutes to get that photo (above) plus several others, and the owl never even flinched. In fact, it was still there about an hour later, when I went around the Drive a second time. (Note, no birds or MNWR reps were stressed during this process.)

Of course, MNWR doesn’t care about any of this. My writing is a minor annoyance that hardly interferes with the photographers, weekenders, home schoolers, sightseers, and unleashed dogs who “don’t believe [their] lyin’ eyes” and spend both time and money supporting a “refuge” that kills its own animals. Go figure.

who monitors the MNWR Friends FB page but who never did figure out

that I had directed him to an Amish egg farmer

and not the leucistic hawk

(published May 19, 2025, reviewed February 14, 2026)

+ Africa, Andy Nguyen, baboons, Birds, Crane, eagles, egret, Fish, Geese, giraffes, hippo, Kenya, lions, Maasai Mara, mirrorless, monkeys, Naivasha, Nakuru, rhino, Uncategorized

(In and) Out of Africa

Africa is beautiful!

Kenya, to be specific.

It was a truly unforgettable experience in many ways, not the least of which was the sprawling Maasai Mara and the incredible diversity of the wildlife it sustains.

I left the Olympus cameras at home. We really wouldn’t be doing much walking, so lightweight gear was not a consideration. Instead, I used the full-frame Nikon d850 and the Nikkor 200-500 telephoto lens. I also brought the d500 along, whose APS-C sensor would give a little extra reach when needed.

I had some trouble adjusting to the mechanical viewfinder. I am so used to the EVF on the Olympus, where what you see is what you get. So, some of my photos were, um, “exposure-challenged.”

See what I mean?

Good thing Andy showed me how to use Adobe Camera Raw! I was able to salvage this cute little bee eater, albeit with some graininess that, had I paid attention to the available light, would not have been an issue. Lesson learned!

But that’s not all I learned on this trip.

I learned that the African savannah was not crowded with great herds of animals dashing about or dramatic life-and-death struggles between predators and prey — despite what we see in National Geographic videos. In truth, we had to search for the wildlife, sometimes for hours and sometimes without success. Most of the animals we did find were in small groups, and although we followed some predators, we didn’t witness any hunts-in-progress.

But the savannah does not disappoint!

We saw lions just about every day. Not only are they King of the Jungle, they are King of the Mara as well. And why not? They are at the very top of the food chain, if not the food web, so lions rule wherever they roam. Period.

We did find a lion guarding a recent water buffalo kill. The day was hot, so he would periodically lumber out from the shade for a meal or a snack. Other wildlife gathered nearby, but none were willing to risk the wrath of the lion by approaching too close. So, they simply waited patiently until the lion had its fill and went for a nap; it didn’t take long after that for the carcass to be reduced to mere bones.

Of course, the Mara was not just about lions, water buffalo, and hyenas. There were lots of birds, big and small. I can’t find my bird fieldbook, so I will identify the unnamed ones once I find it.

(some of these photos were severely “cropped” by WordPress to fit in their frames)

We saw lots of other animals, too.

And, of course there were hippos! Hungry, hungry hippos! Interesting that they spend most of the daytime soaking in the water, coming out at night to forage.

And you don’t want to get on their bad side, just sayin

The broad expanse of savannah was awesome. There were few real roads, only parallel paths where tires from the 4-wheelers had matted the grass. The drivers had to be very careful, because matted grass could be a resting place for baby animals, and no one wanted to interfere with that.

But at other times the drivers had to be very aggressive! River crossings could be downright dangerous at times. It took some skill for the drivers to maneuver the 4-wheelers safely across rocky streams and quick-flowing water. There were several times when I had to close my eyes and hang on tight, hoping for the best!

Like, the time when the driver was struggling to get us across a slippery, rock-filled stream. In the midst of this struggle, one of our number urgently called out STOP! — because he wanted to take a picture of a bird. I suppose it’s a good thing that he doesn’t know how close he came to being ejected from the vehicle by a forcible, well-placed foot belonging to a terrified occupant who was angered by his selfishness (me).

Kenya isn’t all Mara, though. The trip organizer, Andy Nguyen, put his extensive experience and meticulous travel-planning expertise to work and designed an 8-day trip that gave us not only the full experience of Maasai Mara but also an exploration of two lakes, Nakuru and Naivasha, before returning to Nairobi to catch our flights home.

Nearing the lakes, we came across some sparsely wooded areas with enough trees to support some amazing (and amusing) wildlife.

We couldn’t access Lake Nakuru directly, but the ring road provided unfettered viewing.

More funny birds:

Other animals living lakeside included monkeys

and baboons!

The giraffes were really hilarious. I thought these two were a loving couple, but the guide assured me they were not — they were two males fighting over a female! When fighting, they attack the most vulnerable area — the neck. If a neck fracture isn’t fatal in itself, it would certainly cause the injured giraffe to starve to death.

However, there were some giraffes who were behaving nicely:

Surrounding Lake Naivasha is a small fishing village. The animals were amazing. . .

. . .almost as amazing as the villagers

There was only one thing that bothered me on this trip, and that was I WISH I was a better photographer! So many of my photos were duds, and I see lots of areas in these photos that really need improvement. I returned to the States with a task list to work on and with much gratitude and admiration for Andy, who devised this incredible safari. His example as a photographer, teacher, and an honorable man who is true to his word is certainly one that inspires!

Oh, yeah, well . . . there was this other problem, too. Unfortunately, a couple of participants were not satisfied with what the tour offered. Their extensive (expensive!) and divisive demands ruined the social affability we had previously enjoyed. They were pervasive, persistent, and far from silent; they even persuaded one of the driver-guides to take sides in the dispute. Although there was no way to send the troublemakers home while in the middle of the African bush, we simply made the best of a bad situation; however, it is comforting to know that they are banned from attending future tours — and that the aggrieved parties had withheld from the driver-guide his share of the customary end-of-trip tip.

And, I can attest to the success of this policy! I recently attended another Andy Nguyen phototour, this one in Costa Rica, and I assure you the absence of these two was sooooooo refreshing! Costa Rica was almost as wonderful as Kenya, so stay tuned — I will post the Costa Rican results soon.

(published December 13, 2022)

Just past the glitz of Niagara Falls (on the Canadian side) are the Dufferin Islands.

These islands were created early in the 20th century during the construction of a generating station by Ontario Power Generating (OPG).

The area has been a government-administered nature area since 1999, when power was no longer produced there.

The islands are rather small and easily traversable. Paid parking is nearby, and there are benches near the water for those of us who want to check our gear for the proper settings before we begin.

I met my friend and mentor, Andy, there yesterday for a lesson on birds-in-flight. Photographing birds – period – is hard enough, since they never really stay put for every long. You never know when they will take off, leaving just a blurry spot in your photo as evidence of their existence.

Birds-in-flight, though, is particularly challenging. . .for me, anyway. Part of the challenge is that I’m easily distracted by bird behavior, even when they are fairly static and just hanging around.

They’re so funny!

So, while most of the lesson was learning how to pay attention, I did get quite a few useful pointers from Andy, who I swear is the original Bird Whisperer.

Armed with a stockpile of suitable bird food, Andy threw it towards the water, which immediately attracted flocks of Canada geese and ring-billed gulls.

The geese were lazy, not hungry, or both, because only a few of them chased after the food.

In fact, they mostly preferred to gather around our feet, waiting for us to scatter it on the ground.

Even so, they pretty much ignored it.

The gulls, however, were different.

They battled each other, winging and splashing, until the triumphant victor rose above the fray and flew off with the tasty morsels.

And woe to the poor goose who dared to venture out and capture a snack!

It would get a scolding from an infuriated gull for sure!

So, it was a great opportunity for catching some birds-in-flight!

It was sunny at mid-day, so we shot wide open (for me, that was f/5.6) at 1/1600 or 1/2000 with a low ISO.

Andy advised a 4-stop difference if filling the frame with gulls (all that white would drive the meter crazy!)

But that would be a rarity for me.

At this point, I’m happy just to get a bird in the frame that is recognizable as a bird!

Unfortunately, I did get a good amount of blurry blobs but eventually managed some decent shots, especially after Andy changed my focus setting to group. . .

. . .and coached me to try to keep the focus pont(s) centered on the bird.

That worked a lot better!

These birds may be “just gulls,” but they are living, breathing creatures doing what they are programmed to do.

And they do it beautifully!

Maybe not as colorful or rare as other birds, but good subjects to practice on. . .and amazing creatures in their own right.

Butt shots are not acceptable in the good-photographer community.

However, I couldn’t resist this one with his tail so strategically elevated in the perfect position for a quick takeoff after landing and grabbing.

I think the duck was utterly surprised!

I worked reallyreallyREALLY hard on focus, which seemed to elude me despite my best efforts.

Another Andy tip — when focusing on BIF, “pump” the focus button. This will help keep a fast-moving bird acceptably sharp.

Back-button focus works well here, and I was pleased that I was able to set BBF without Andy’s help. 🙂

This tip worked well, so well that I was able to crop some of my photos for close-ups.

Just before we had to leave, in flew an adult black-crowned night heron! They call them “night herons”for a reason, so it was great to see one in the middle of the day.

Andy’s photo is much better than mine (he caught the red eye by moving to where the sun would catch the heron’s eye and light up the retina).

But I am happy with mine. The focus is good, and the heron is preening.

“Preening” sounds much better than “scratching at feather mites,” don’t you agree?

Anyway. My next lesson will be on reading the light.

But I need some practice first!

In case you are new to this blog and don’t know who Andy is, he is a phenomenal photographer who both teaches and offers higher-end workshops. His main interest is nature, specifically birds.

He really IS the Bird Whisperer, not to mention the Gear Guru.

Take a look at his photos, and I think you will agree.

(published July 9, 2022)

Been taking my camera out as often as I can, experimenting with manual mode.

And lighting. That seems to be my biggest problem.

There was a particular grainy, 18% gray day this week, where everything came out fuzzy and monotone. Like this guy over here ———>

I went back on the next day, which was bright and sunny, and did much better. Like that guy down there. . .same greenie, better light so better focus.

Even phase-detection focus points need some sort of contrast to work effectively.

So, I’ve got to learn how to make the best use of available light. . .which may mean just waiting until there is enough of it to work with.

That, and birds-in-flight. Andy gave me some great tips, but it’s putting them into practice that’ the problem. . .

The first — and most important, I think — is to focus on the bird in the distance, before it takes off.

If you wait until it’s in flight and then try to focus, it’s really hard to get a good lock. . . reallyreallyREALLY hard.

Maybe not for others, but certainly for me.

Another issue: I’ve GOT to learn not to underexpose.

The lack of suitable subjects is frustrating. This has been worsening ever since I got back from Florida.

There were sooooooooooooo many birds in Florida! Here in western NY?

Not so much.

I’ve been spoiled!

I have only two nearby wetlands, and they are not very nearby. Each takes about an hour to get to.

Montezuma National Wildlife Refuge used to be my go-to birding place.

It has a 3-1/2 mile Wildlife Drive, which used to be a rich source of wildlife. On either side of the Drive there are wetlands, a marshy pool on the west side and the Seneca Canal on the east. As the Drive curves around to the west and south there are smaller bordering pools.

Or, what used to be pools.

You see, the marsh managers think it’s a good idea to drain the marshes every spring, which dries up a vital element of the food web.

They’ve been doing this for the past 5 years.

Indeed, the last year there was any appreciable water in the marshes was 2017!

The wildlife aren’t stupid.

The herons, eagles, osprey, kingfishers, etc. who at one time frequented this Flyway stop, simply look elsewhere for better fishing grounds.

This year it’s been virtually deserted, except for a delightful sandhill crane family, who thrive searching the meadows-that-were-once-marshes for edible goodies (but usually on the bad-light side of the Drive!).

Of course, there is also the occasional great blue heron, an eagle or two, and a rare pie-billed grebe. And yesterday I saw two great egrets — but way out in the main pool, where there was a decent water level.

There’s always hordes of redwing blackbirds, purple martins at the feeders (in season), song sparrows, kingbirds, and a few warblers (again in season).

And geese. There are always far too many Canada geese!

The (formerly) good variety of shorebirds, which included a pair of Wilson’s phalaropes (!) are long gone, now that their feeding grounds have dried up.

Anyway

My other go-to area is Sterling Nature Center.

No Wildlife Drive here, but certainly some very good trails, one of which takes you to a great blue heron rookery.

This is always a great place to visit!

Especially in the spring, when a variety of flora and fauna can be found and the herons are busy raising their young.

I am going to get busy and search for new hunting grounds, some close by and some farther away.

Stay tuned!

(published June 14, 2022)

Wild Wings Florida 2022 ended with me totally convinced I should move there. . .until I remembered that the cockroaches are this big <<holding hands out wide>>

Here are some more shots, some good and some not-so-good, that I took on that wonderful Last Day of Wild Wings Florida 2022:

(published May 30.2022)

Recent Comments